I suspect my background in teaching is a very common one. I moved from teacher through a series of middle and senior leadership positions until I was a deputy head. As a result, when I first became a school principal, I focused on what I knew; namely the processes and strategies which I’d seen to be effective. This included a focus on teaching and learning, parental engagement strategies, quality assurance procedures as well as assessment routines and so forth. But looking back it is now clear that, whilst these were incredibly successful, to a large extent they were all individual strategies and instruments, rather than an holistic approach.

During that first term, with new learning protocols in place and staff offering both on site and remote learning, the focus became staff wellbeing. Teachers across the world were being asked to teach in a totally new way, using unfamiliar technology, yet being asked to perform at previous levels of success. As a school we recognised that if this was going to be sustainable (and there was significant doubt about this) we needed to ensure staff were properly supported in this new context. Very rapidly, this focus extended to looking at the culture of the school. As well as putting well-being strategies in place we wanted to identify how the school could be led from an holistic perspective.

Over the last 18 months this has become an increasing topic of fascination. There is significant writing on the impact of organisational culture within a school and, whilst there is inevitable disagreement about many aspects of this, that this is a powerful force for school improvement is rarely challenged.

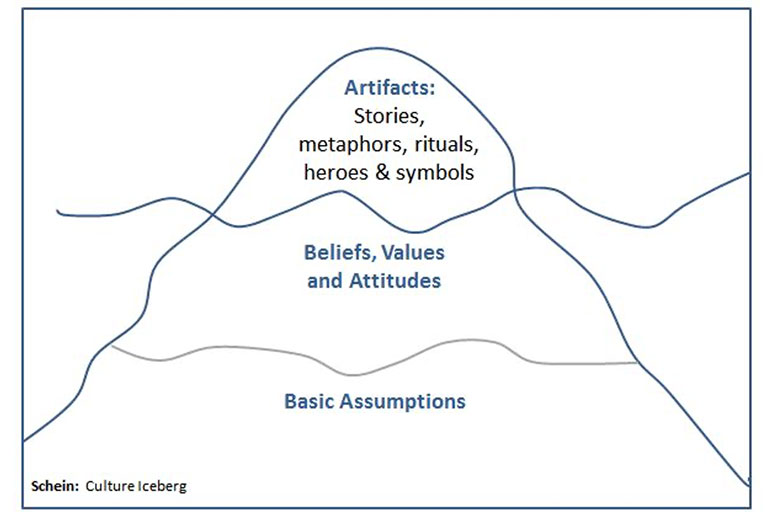

The concept of organisational culture is a familiar one in the corporate world and many will know the observation of Peter Drucker that ‘Culture eats strategy for breakfast’. Furthermore, one of the key authors on organisational culture, Edgar Schein, wrote ‘the only thing of real importance that leaders need to do is to create and manage culture. If you do not manage culture, it manages you

The unique talent of leaders is their ability to understand and work with culture; and that it is an act of leadership to destroy culture when it is viewed as dysfunctional’. Toby Greany and Peter Earley even went as far as warning: ‘To neglect a considered and structured response to culture is perilous to the point of being foolhardy’. In a school context, with the enormous array of responsibilities within the headteacher’s job description, it would seem something of a challenging statement that their only real responsibility is to manage the culture of the school.

Organisations such as Credit Suisse and HSBC have worked to construct cultural models against which all actions can be judged. However, this is far less common or known in an education sector which has traditionally rejected such initiatives for exactly the reason of being ‘too corporate’. However, as I hope to show, this is an approach which can fundamentally impact the leadership of a school.

To accept this, there needs to be an understanding of what is meant by the term culture. Again, previous authors provide a number of answers. ‘Culture is the values, norms, beliefs and customs that an individual holds in common with members of their group’. Or that ‘Culture is to the organisation what personality is to the individual – a hidden yet unifying theme that provides meaning, direction and mobilization.’ Certainly, one of the challenges of dealing with organisational culture is that it is difficult to precisely measure, but when one considers it in terms of both values and personality, I believe its potential power becomes clearer.

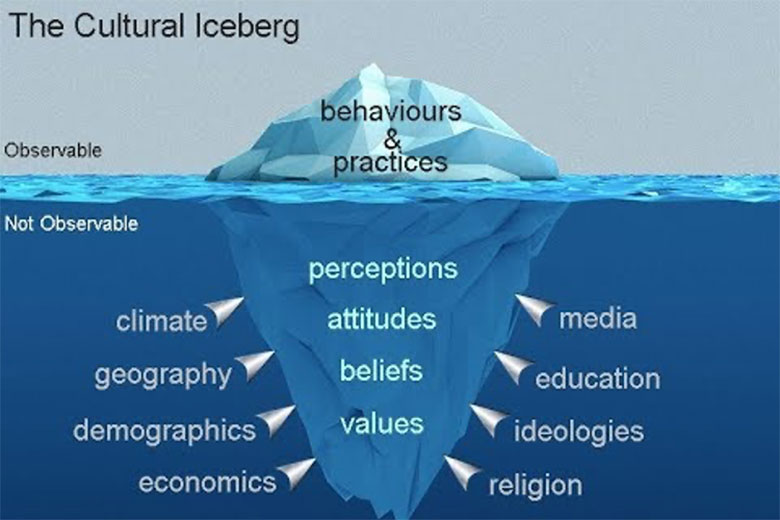

Culture is also recognised to exist in an organisation at various levels. Edward Hall referenced this as a Cultural Iceberg. At its most obvious and visible, culture manifests in the behaviours and practices that exist across an organisation. Within a school context this can be the more obvious elements such as school events, policies, calendar of events but also lies in the less formal practices. For example, it could be in the way in which members of the SLT interact with staff. Are they visible around the school? Do they have open door policies in terms of meeting with staff, students and parents? How transparent are the school policies?

But beneath this lie the less visible, less tangible elements which underpin the observable behaviours. This could include the vision and mission statements of the school. It also includes the assumptions upon which these statements have been made. For example, does the school value inclusion, equity and diversity? Is the school selective or non-selective? Does the school exist as a for profit organization or not for profit? These values, and the extent to which they are prioritised, will inevitably impact the behaviours which go to make the culture visible to others.

In addition, if an organisation’s culture is to be managed and effectively embedded, then these elements must be identified and considered if to be successful.

Drucker’s suggestion is that management of organisational culture is more impactful that any strategic interventions. This has certainly been our experience over the last two years. Simon Sinek, the bestselling author of ‘Start with Why’, ‘Leaders Eat Last’, ‘Together is Better’ and ‘The Infinite Game’, has helped and inspired organisations worldwide to reach new heights. In the second article in this series I will outline Sinek’s perspectives and explain how they are equally appropriate, and impactful, for the leadership of a school culture.